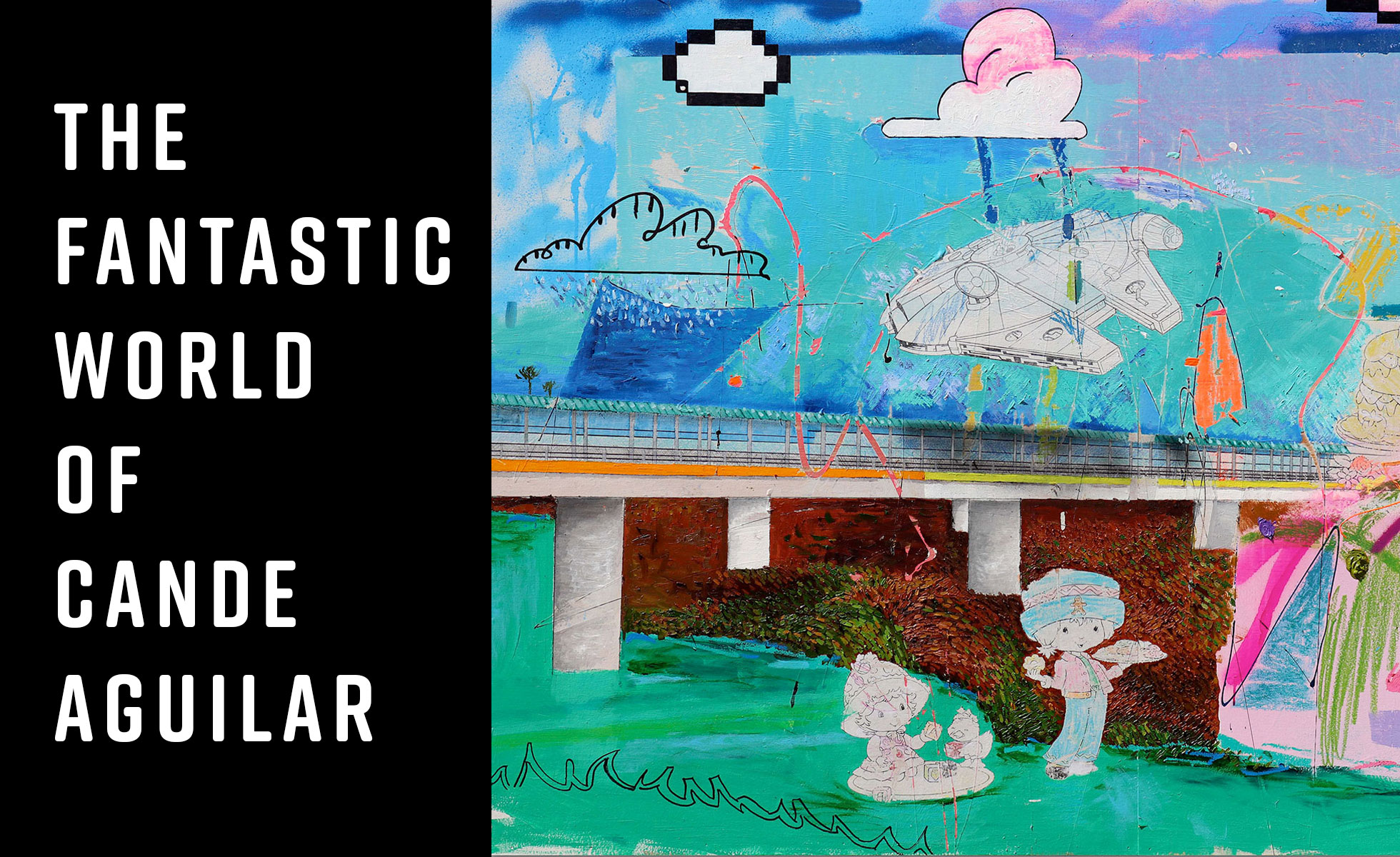

The Observer: The Fantastic World of Cande Aguilar

The Observer: The Fantastic World of Cande Aguilar

by Michael Agresta

December 16, 2019

When rising Brownsville artist Cande Aguilar was invited to show his work in his first solo New York City exhibition, in September 2019, his excitement was tempered by a major new obstacle: how to ship his large paintings and sculptures across the country. The nearest art handlers he could find were in San Antonio. Just to get them to come to the Rio Grande Valley to pack up his work would add a hefty out-of-route fee.

“The infrastructure, it’s just not here,” he says of life as an artist in Brownsville. “As far as I know, nobody’s ever actually had a solo show in New York being from here, working out of here.”

Noah Becker: Your work is very direct – what do you think about when starting a painting? Or is it a process of thinking in multiple ways about groups of paintings?

Jason Craighead: I tend to think of my entire practice as one idea versus different topics. That being said, I find myself seeking “moments” in my process which does lead to “groups” of works that are tied together through aesthetic language. I don’t think in “series” … maybe when I look back I will see “periods”. The “thinking” part never leaves.

Becker: My recent goal has been to NOT compare artists to artists in art history. So in that spirit I will ask you where you find inspiration?

Craighead: I have always felt inspired by, to put it simply, things that move me … everything from a gorgeous work in a museum to some half covered graffiti in an alley, songs, poems…human expression in general. I do believe my aesthetic comes from the place of expressionism, when artists began to break loose from “recording things” and allowing the process of “making” things to come forward in the work. We are all standing on the shoulders of those before us.

Becker: Do you make a lot of drawings? Your paintings have a wonderful connection to drawing as they are. How do you see the difference between drawing and painting?

Craighead: I am forever enamored with beautiful drawing marks….I used to believe that my works on paper were “drawings” until it became clear to me that they were the same as my works on canvas. I find the drawing in my works to be a nice “guide” for the viewer to move them through the composition. I’m not sure I would care to do one without the other…so maybe drawing and painting have melded together as one thing for me.

Becker: How do you think about color or the absence of color in painting?

Craighead: I feel that there is never an absence of “color” in any and all things—if you can “see” it then it is there. In it, under it, throughout it … whatever “it” is. WM

There were no art museums in Brownsville when Aguilar, 47, was growing up. “The mom and pop stores, their hand-painted signs, they were my museum,” he says. “Then the contrast between going to a mom and pop store, and then going later that day to McDonald’s, where everything is so hard-edged, perfectly designed, and the colors are so consistent—that fascinated me.”

Aguilar’s mother worked at El Centro, a grocery store that Aguilar describes as halfway between a true mom and pop and the corporate chain stores that now predominate in the Valley. His father—when not performing onstage as the longtime bass player of conjunto band Gilberto Perez y sus Compadres—occasionally painted houses, bringing the younger Aguilar along to help. “The idea that I had to cover the space evenly, something as basic as that, that’s the foundation of the work,” Aguilar says.

At 6 years old, Aguilar received an accordion as a gift. He treated it as a toy at first, but around age 10, he began to take it more seriously. Aguilar’s godfather, Gilberto Perez, was a prominent conjunto accordionist and his father’s bandleader. For a kid, getting to watch Perez and other members of the band play was “like watching Picasso paint,” Aguilar says. “I experienced these real masters. The access I had to it gave me the confidence to realize I could be an artist. That was the door that I opened and stepped through, and I was in the art world.”

His first entrée into the art world wasn’t painting, but music. Aguilar taught himself to play accordion by studying the great conjunto artists—listening obsessively to his father’s record collection, practicing, and returning to the records when he had questions or wanted to add to his repertoire of styles. Before long, he was able to accompany the Compadres onstage, and at 13 he cut his first album.

In the summer of 1988, after his sophomore year of high school, Aguilar toured with the Grammy-winning Houston band La Mafia. The opening act was a not-yet-famous Selena, who would soon rocket to fame as the ill-fated and much-beloved “Tejano Madonna.” Aguilar captured one of those teenage dressing-room memories in a painting, “Encuentro with an Angel.” The composition shows a well-coiffed cartoon version of himself alongside a ghostly ballet dancer, who leans on his shoulder as she stretches her leg, as if warming up to go out onstage.

After that summer, Aguilar would return home to finish high school, a priority for his family. His fortunes in the music industry never again rose to the same stratosphere as Selena’s, though his band, Elida y Avante, had a good run for nearly a decade, touring consistently and scoring a gold record. They broke up in 2000, shortly after winning several Tejano Music Awards.

The first year after the band’s breakup wasn’t easy for Aguilar. He worked a literal graveyard shift, gardening overnight in a cemetery. “It was hell, after getting off the stage, seeing myself watering a cemetery,” he says. “I was walking around with a broken heart.”

The Observer: The Fantastic World of Cande Aguilar

“I feel like I’m this normal guy, but I’m also this other weird guy who makes art,” Aguilar says. JOHN FAULK, FRONTERA MEDIA

“La Lucha,” 2019. CANDE AGUILAR